We’re off to the big white dyno at Lake Gairdner for speedweek 2015.

The image is of Brett Destoop, fastest man in Australia…… and the world in the APSF-1000 category. 232 MPH (371 km/h) Lake Gairdner. Thanks to Simon Davidson for allowing me to feature his image. You can see more of Simon’s work at his website.

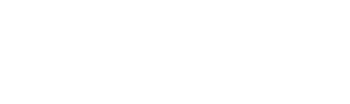

Skrunkworks will be campaigning Assalt – based on a 1987 BMW R80 with 1000cc barrels and heads. We will be entering the 1000cc pushrod, unfaired (no streamlining), gasoline, category.

It’s hard to be realistic when your brain is pumped with the image of records shattering like glass as you scream across the salt… Thankfully, testosterone has settled back to default levels of egomania and sensible but vaguely irritating thoughts are invading like: ‘Greater men and women have gone before…’ and ‘this is going to be a 2+ year exersise...’

Update 03/07/2014: We are well underway working through the wish list put together in 2013 (below). Follow the progress on our blog or facebook or instagram

- Gearing may be an issue: with a taller aftermarket 5th gear and the longest rear bevel drive available (32/11), we’ll probably need to spin the engine to 9000 RPM.

- Cam: There was a time in the 1900’s that the only off-the-shelf ‘hot’ cam that you could get for an airhead was BMW’s own 336 ‘Sports’ cam. Things have evolved and now there are several modern grinds available – mainly out of Germany. I’ve got my eye on a 340 degree high end race cam…

- Crank will remain stock but balanced to lighter con-rods and light, high compression pistons. Static CR will be around 11:1

- Lightened valve train throughout.

- Inlet valves enlarged to 46mm.

- Exhaust headers enlarged to 41mm or more.

- Heads ported to suit new valve sizes and dual plugged.

- Dellortos – probably 40mm.

- Modified oil pump to counter possible cavitation problems at high RPM’s

- extend sump + oil cooler.

- Wave tuned inlet and exhaust tract lengths.

- Delete the alternator and run total loss ignition (starter can stay – weight is not such an issue since there is 3 miles to accelerate to speed)

- Stiffen the rubber cow’s frame – no tank slappers at +200km/h please.

- Extending swing arm to improve straight line stability.

- etc. etc – lots of them!

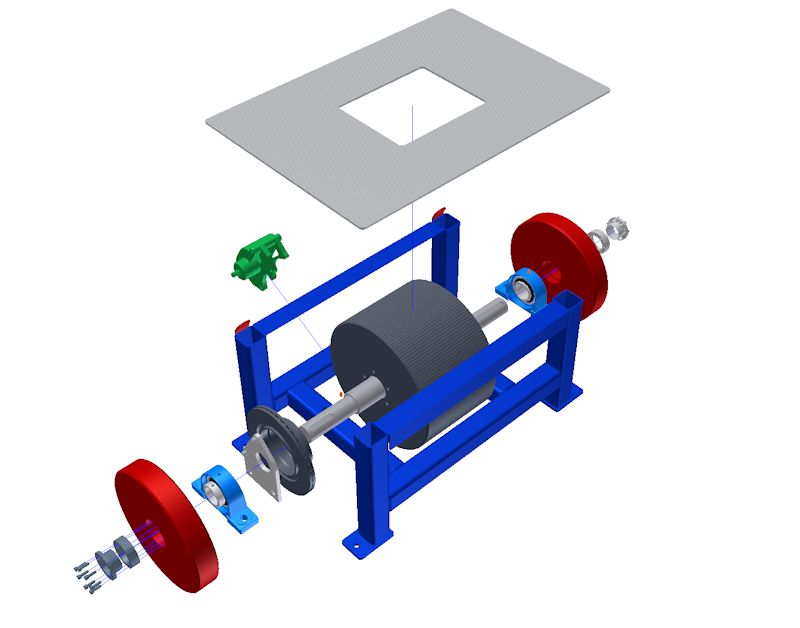

So, there’s lots to do including building the dyno and dyno room and it remains to be seen how we’ll fair leading up to the Feb 2015 crunch time, but one thing’s for sure, it’s going to be fun!

Update: 03/06/2014: Frame stiffening completed

My shed mate Ross of Supacustom has hooked up with an old compadre of mine, Paul Chiodo of Peter Stevens Motor cycles.The pair will be campaigning a Triumph Bonne of noughties vintage. Ross will be responsible for modifying the rolling chassis while Paul and his cohorts will be herding a bunch of wild horses through to the back wheel via various highly modified mechanical contrivances.

We’ve got heaps of work to do including building a dyno and dyno room! So strap yourselves in for an epic ride of a blog and PLEASE, leave comments and suggestions – doG knows we’ll need them!!